43 years ago today we started production on the groundbreaking television show Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman. I played Heather, Mary’s angsty tween-aged daughter – a role that forever changed my life in many wonderful and tragic ways.

I was incredibly fortunate to be on a cult hit with whip-smart, hilarious actors who expected me to work as hard as they did. I was beyond lucky to have an extraordinary tutor who actually educated me and broadened my intellectual horizons, while protecting me to the best of her abilities. There were many adults in the crew who allowed me moments of pure childhood fun on a super-adult show whose mission was to violate the entire Code of Practices for Television Broadcasters.

Even with all of these well-meaning adults looking out for me, my parents exploited me, as is the case with SO MANY child performers.

I was the face of ‘Lively Lines’ – it was part of Mattel’s first art-educational toy line, called Imaginings.

In 1975 I was an 11-year-old Fountain of Money, and my parents had been stealing my paychecks since I was 3. I had done so much work that I was able to get my Screen Actor’s Guild union card when I was 5, and my AFTRA card at age 7. In 8 years I’d done nearly 60 commercials and a few television feature spots. I’d booked dozens of print jobs and voice over gigs, I was on a candy bar wrapper, and I was the face of a Mattel toy – not a very popular toy, but, still…

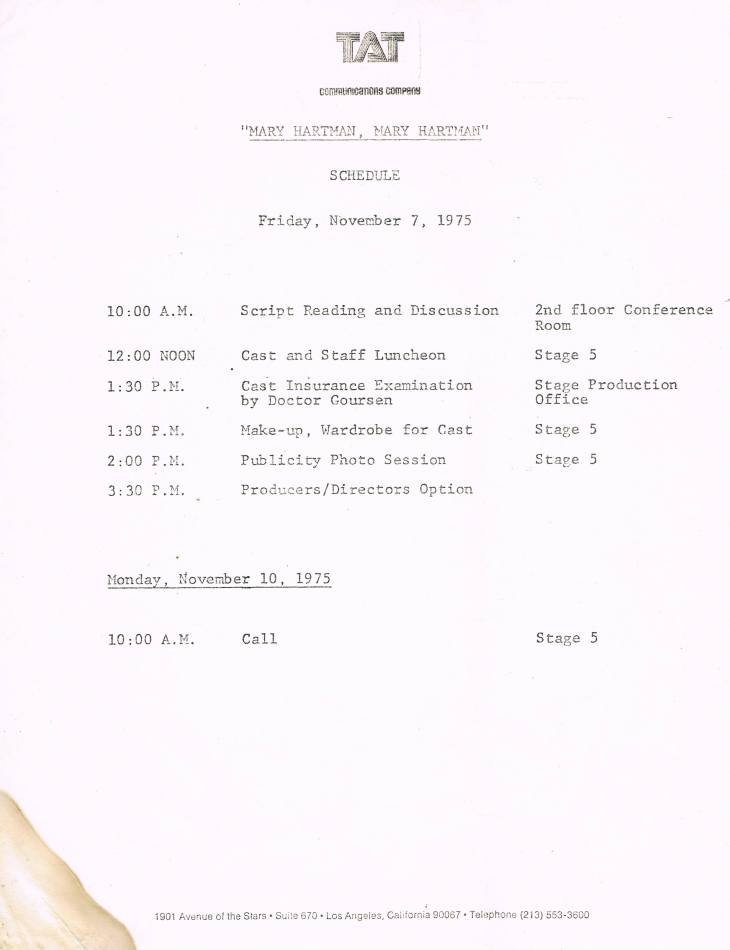

I came to be part of Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman at the last possible minute before production got underway. I went on the interview Wednesday November 5th after school. I got the call back and was offered the job on the evening of Thursday the 6th. On the morning of Friday the 7th I was sitting dazedly at the first table read on the lot at KTLA, on Sunset Blvd.

In 43 hours my life had turned on a dime.

Our first Call Sheet

Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman was the brainchild of television legend Norman Lear. Presented as a soap opera, MH2 was Lear’s grand statement on American Consumerism, and how marketing isolates us by targeting our fear of inadequacy. It was his poke in the eye to conventions, censors, and Pearl Clutchers.

In 2 seasons we shot 325 episodes of Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman. It was a half-hour show that aired 5 days a week, and had a cult following that goes on to this day. When Louise Lasser left the show we continued on for one more season, filming another 130 episodes under the name Forever Fernwood – the name of the fictional town where the series took place. In total we filmed 455 episodes in 28 months.

MH2 was the first television show that proved you didn’t need a network to succeed or a laugh-track to be funny. It challenged sexism, racism and prevailing morals. It also introduced multiple positive LGBTQ characters to television at a time when Harvey Milk had not yet been elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. It is not overstating to call MH2 an unprecedented and revolutionary television show.

The list of exceptional performers who appeared on Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman and Forever Fernwood is a who’s who of funny and talented people from the 1970s: Louise Lasser, Mary Kay Place, Martin Mull, Fred Willard, Dabney Coleman, Doris Roberts, Dody Goodman, Graham Jarvis, Greg Mullavey, Salome Jens, Ed Begley, Jr., Howard Hessman, Shelly Fabres, Shelley Berman, Richard Hatch, Tab Hunter, Sparky Marcus, Marian Mercer, Gloria Dehaven, Orson Bean, David Suskind, and Gore Vidal – just to name a few. It was just that cool at the height of its popularity that a cameo or a brief story arc was sought after by the biggest names in the business.

At one point Steven Ford, President Gerald Ford’s son, wanted to just come to visit Stage 5 to watch us film. Everyone was atwitter about such an important visit, until we found out not enough of the cast or crew could pass an FBI background check to allow Ford to visit the set for even one day.

The only reason I ended up in such rarefied air on the set of MH2 was because my mom had blown up at my agent, Iris Burton, for not getting me any good interviews.

Mind you: I had just landed five commercials in six months – including a Nestle’s $100,00 Bar spot that was a gusher of residuals (and would be for the next 6 years). But my mother demanded more from my agent. She wanted better interviews and she demanded more readings for movies and television series. There were shouted threats of moving the fountain-of-money-that-I-was to different representation.

A few days after their angry conversation I got the interview for Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman – and it was nothing less than a grudge interview. My agent had submitted me for the role of a 13-year-old who was overweight and busty, a frizzy haired girl with bad skin. I was 11, skinny as a rail, with no figure at all. I had long braids and glasses and silky smooth skin. Iris had secured an interview for a role I was simply unsuited for as a way to show my mother not to question her judgment.

Two grown women were using pre-pubescent me as the badminton birdie of their avarice and rage.

The interview for Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman was not-quite a Cattle Call, but there were dozens of young women ahead of me – not a one of whom looked like me. I was given a ‘side’ to study after I signed in, and glanced at it. (A side is a mini-scene for audition purposes, usually 2 or 3 pages long. These days it can also refer to the pages of a movie script that will be shot on any given day.) This side was a piece where the mother (Mary) is trying to talk to an unwilling daughter (Heather) about sex, and the daughter manipulates her mother by redirecting the conversation to make it seem like she doesn’t even understand what sex is, which relieves the clueless mother to no end.

I completely understood the piece the first time I looked at it. I got the joke.

Unfortunately there was a long wait, and my mother was determined to coach me to death, as she did with every audition. She would drill me again and again on how I should say my lines and move my hands, and I every time I went through that door to an audition I ignored all of her terrible advice and did it my way.

There was nothing special at all about this interview, it was just another long afternoon with my mother, and I had no idea how it was going to change my life. It was simply one more of the fifteen or twenty auditions I went on every month. My time was never my own – it was more an all-consuming continuum of school, cars, auditions and work.

When I was finally called in to the interview, after at least an hour’s wait, I turned ‘on’ like a light switch. I was a pro. I knew how to look the casting director in the eye as I was crossing the room and saying hello with a smile and a slight nod, and to keep eye contact as I handed my litho forward, right-side-up with my name at the bottom. I had literally done this 1,000 times before.

The casting director introduced herself as Jane, and the Director as Joan. There were other people to whom I was not introduced, and who watched silently as I read the scene with Joan. Joan nodded when we got to the end of the scene, and asked me to do it again – this time miming the orange juice I was supposed to be getting out of the refrigerator. We did the scene a second time, and I a saw the ghost of a smile from Joan.

Jane asked if I had any other auditions that afternoon, or if I could stay to watch the two pilot episodes of the show. Hearing that I was free the rest of the afternoon, Jane sent me to get my mother from the waiting room. Mary Margaret Lamb took a long moment to fold her knitting project and stow it in her bag before doing a positively graceless ‘My Kid Is Better Than Yours’ sashay through a sea of angry parents and dejected children.

We were led to a cold office, and we sat on a couch looking up at a monitor on a large metal rolling stand. The screen flickered to life and the episode began as a nearly sepia-toned video of kick-knacks on a table came into focus, and with it the swelling of over-dramatic music saturated with high-pitched violins. Out of nowhere a voice that could cut glass screeches, “Mary Hartman! Mary Hartman!!” so shrilly and gratingly I physically winced. Then came a gush of overwrought music heavy on the strings, parodying the soundtrack of really bad soap operas.

It is a distinctive open. Oh, so distinctive. I was tormented in High School with people shrieking it at me as I passed them in the hall. I’ve had grown-ups shout it in my face at parties as if I’ve never heard it before. I’ll bet you I’ve heard, “Mary Hartman! Mary Hartman!!” ten thousand times if I’ve heard it once.

Torture yourself, if you’ve never heard it.

As I watched the pilots I clearly remember thinking, “This is weird.” My mother didn’t know what to make of it, either. The lack of a laugh track threw her off, and I remember her saying later she didn’t know if she was supposed to be laughing at things or not – especially the inappropriate subjects.

It was late when I read for the folks in the room a third time, and they thanked me as I left, asking if I had any bookings in the next week. We drove home in the dark, and – exhausted – I didn’t get my homework done again.

The next day after school I was crying in my bedroom, sitting on my bed unsuccessfully trying to figure out what my algebra book was saying. It had been a bad day. 10-Week Grades had come out and my algebra marks were poor from never having time to do my homework. I was struggling mightily in math and had gotten a D, and my mother’s answer was to verbally and physically abuse me. I was grounded (as if I ever had time to go anywhere), and sent to my room to magically figure out the integers and angles I couldn’t decipher before.

Suddenly, my mother burst into my room without knocking, making the door crash against the wall. Privacy didn’t exist in my home as a child – and at that point I was not allowed to even fully close my door, lest my mother not be able to keep an eye on me at all times – and crashing doors usually meant more verbal abuse or hitting. I cringed, throwing my hands up around my head to protect myself from the expected blows. Instead of being wild eyed mad, she was wild eyed excited. She didn’t get angry at me for protecting my head like she usually did, and ignoring my cowering she said manically, “Get dressed! You’re late for a callback! They want to see you back from yesterday, but they forgot to call Iris to set it up. Hurry!! We should have been there at 5 pm. Where are your clothes?”

She was no longer hurling invectives at me, saying how stupid and worthless I was. She seemed to have forgotten the blows she had delivered to my head and back just minutes before, and was eagerly telling me to get ready.

My clothes from the interview the day before had been stuffed into the red laundry bag my mother had crocheted, and they were wrinkled. Frantically she snatched them from my hands and threw them in the drier to tumble out the wrinkles. She brushed and braided my hair, while having me hold a cold washcloth to my face to erase the swelling and redness from my sobbing.

“C’mon – you’re not really going to go in there looking like that!” she admonished, catching my eye in the giant round mirror above her sink, “Where’s your apple pie smile? Smile like you mean it – smile with your EYES!!” she encouraged/threatened me, as she pulled my braid too tight.

She was so focused on getting me to look exactly as I had the day before that she didn’t run a comb through her own hair, and she rushed out the door without changing out of her dirty black slacks and grubby sweater. For a woman so defined by façades, my mother’s slovenly appearance that evening when she first met Norman Lear and Louise Lasser would torment her for the rest of her days.

Before I knew it we were out in the middle of rush hour traffic, heading over the hill on the Hollywood Freeway. It would take at least an hour to get there, and I was trapped in the car with a woman who was vibrating from excitement, drilling me over and over on how to do the scene her way.

Such was the Emotional Roller Coaster of my youth: Half an hour before she was screaming at me and hitting me about a bad math grade that might keep me from renewing the all-important California Work Permit, and now I was running lines her way and being told not to blow it because this could be The Big Break.

But beyond all that detritus and noise, there was euphoria about getting a callback for a Norman Lear series.

When we finally arrived we were waved on to the lot to park and I was rushed into Norman Lear’s office where he, Louise Lasser, Director Joan Darling, producer Al Burton, and writer Gail Parent were waiting. I made eye contact and gave them my apple pie smile, pretending my head didn’t hurt where my mother had been punching it 90 minutes ago.

I read the same side as I’d read the day before, only this time instead of reading with the Director I was reading it with Louise Lasser. Suddenly the scene was done, and they told me ‘Thank you, you can go’.

Thank you, you can go? But – we’d only read it once. How could it be ‘Thank you, you can go’?!

In less than 5 minutes I was in and out, and I found myself heading toward the elevator in dismayed shock, not understanding how I had failed so completely and astoundingly fast when it felt like a good read. I knew it was going to be a long, ugly ride home.

We were getting on the elevator in silence when Al Burton called my name down the hall. I heard the smile in his voice and I knew I had the job. My heart hit my feet as I stuck my hand out to stop the heavy elevator doors.

Al caught up to us and said they all really liked the way I read the part, and then he asked if I wanted to join the cast. “The job yours if you want it,” he said, smiling and looking me in the eyes like I mattered.

I remember gasping and jumping up and down. I remember saying, “Yes!!” and bear hugging Al, and then hugging my mom as she beamed and rocked me back and forth in that elevator.

I remember being happy – happy in a way you can only be when you’re too young to be wary and you don’t have the adult filter that stops you from showing what you really feel. In that moment I was validated for all the times I wasn’t chosen, and I felt special because this time I was the best. I was going to be on a Norman Lear TV show – and it felt like winning.

I don’t think that there was ever a time in my life that my mother was more proud of me than that evening in the hallway outside of Norman Lear’s office.

Being cast on MH2 changed my life completely. One day I was attending Junior High school in the most polluted part of the San Fernando Valley, and the next I was sitting at a long table in a conference room at KTLA, meeting my cast mates and production people. We were given our scripts for episodes 3, 4 and 5 and did the first, last, and only table read we ever did for the show. There was never time after that initial day for the luxury of such a thing.

There was a lady there who took care of timing out the scenes and continuity named Susan Harris who had the patience of Job with me. I was absolutely fascinated by the cigar box full of gum and mints (Wow! Tic Tacs!) that she kept with her at all times. I must have looked like a chipmunk with all the gum I shoved in my mouth that morning. She was kind to an antsy, nervous kid.

We started in on the table read, and I was bored stiff by the time we were done reading the 3 scripts several hours later. It was an excruciatingly long exercise, and somehow something as simple as reading words printed on paper turned into a thing. Everyone was making a WAY bigger deal out of it than they needed to, and many hairs were split. I know now that everyone was staking out their territory, and planting flags for their characters, but it was painfully long and ego driven. That table read became the template for the rehearsal and taping of nearly every episode of the show.

After the water-torture of the table read we all went down to Stage 5, where a luncheon was held for the cast and the production people. It was catered by Chasen’s of Beverly Hills, a perennial favorite of Norman Lear. There were place cards, and I was seated up at one of the front tables next to Debralee Scott and Dody Goodman, while my mother was seated far in the back where I (thankfully) could not see her.

All of us had individual goody bags which were filled with kitschy things. My bag had a draw string and was sewn to look like a pineapple. It had a plastic charm, 4 tickets to the cancelled children’s show Sheriff John, a pack of stale gum, some ribbons, an Oscar Meier Wiener whistle and some other junk. Everyone else had similar stuff. Although I didn’t fully grasp it at the time, it seemed to signify the budget we were working under.

The adults all seemed to know each other, and as they laughed too loud at inside jokes I tried too hard to be part of the group. I saw Louise again, and spoke for a while with Greg Mullavey, the man who would play my ever-adolescent father. Dody was charming and welcoming, and she and Phil Bruns (a grumpy man who had the sour smell of an alcoholic) played my meddling grandparents. Debra Lee, who played my oversexed Aunt Cathy, was a social butterfly who swore like a sailor. I spoke very little that day with the Victor Killian, a quiet man cast as my great-grandfather, who I would come to know and love as the grandfather I never had. Mary Kay Place and Graham Jarvis were delightful, down-to-earth people who played the neighbors: an unlikely crazy-in-love couple, where she was a smoking hot aspiring country-singer and he was a balding middle-aged man who would give you the shirt off his back.

After lunch we were prodded by a strange doctor so that insurance could be taken out on the production. As each of our physicals were completed we got into our wardrobe, and headed off to hair and make-up. My wardrobe consisted of the same pants, shirt, belt, bracelet, braids, barrettes and glasses I sported on the audition and callback – I can actually say I created Heather from the ground up.

We gathered for the cast publicity shot in the Shumway kitchen set, and as each new person arrived in character there was laughter and camaraderie. At that point in the afternoon we were giddy from it all and the slightest thing would set us off in gales of laughter.

The photo we took that afternoon is iconic, and a giant blow-up of it sits behind Norman’s desk, a profound tribute to our show, given the sheer number of them Lear has produced.

That afternoon all of the adults were as kind as they were capable of being to the young stranger they’d just met who had been hired to play a smart-assed, cynical tween. I may have been carrying the weight of being my family’s Fountain of Cash, but my cast and crew mates couldn’t see that. I was a child they’d just met, and they were more focused on how to make this show work when it was so different than anything else on television. They knew we only had 10 days to get mentally ready for the start of production, and the grind of memorizing, rehearsing, blocking and filming 125-150 pages of dialogue PER WEEK.

As for me? It never occurred to me that Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman was going to be anything other than a smash hit.

My new-found station in life brought with it a well deserved bonus. Some frosting on the cake. A little something something for signing a contract on a daily AFTRA television series.

As an atta-girl for being cast on Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman my parents saw their way to granting me a one-time bonus of the princely sum of $5 and dinner at Diamond Jim’s.

My break down was: $1 for a print job, $2 per commercial plus $1 extra if they make 2 spots out if it, and $5 (American!) for a series.

$5 for a series!

I didn’t get a regular allowance until I was 12-years-old, and even then it was only $2 on a $750 weekly paycheck. I’ll do the math for you: In 2018 dollars that’s me getting $9 a week allowance for a paycheck of $3,350.

I was truly a Bellagio Fountain of Cash.

I remember feeling so grown up the night we went to Diamond Jim’s, a past its prime cocktails-and-red-meat establishment on Hollywood Boulevard. Proud of my accomplishment, I boasted to the server as he led us to a high backed red leather booth that I’d ‘gotten’ a television series. He kept the celebration going with an endless stream of Shirley Temple’s (extra maraschino cherries, please!), while I’m sure my parents thought “Great! Now we have to tip appropriately.”

I imagined this would be a grand evening, like a supper club out of a 1940s musical. But the place was filled with smoke, there was no floor show, and they didn’t have any food for children. Diamond Jim’s was a stuffy disappointment after all the build up. My whole family should have gone to Shakey’s Pizza, followed by a trip to Farrell’s Ice Cream Parlor for a Zoo. Instead, my parents isolated me from all of my brothers and created resentment where none ever needed to exist.

The truth is that this was a restaurant for my parents, and I was just tagging along on their celebratory dinner because I was footing the bill.

I ask you – Which was more insulting? A $5 payoff for landing a union gig, (Oh, irony! Thy name is Unionized Child Labor!) or the 3 of us celebrating the impending plunder of my hard-earned money?

Assholes.

That night I felt like I was a successful grown up, and in a way I was. I may have only been 11, but I had a 26 week guaranteed Union contract as a regular on a series. With that contract and my commercial residuals I would earn more than double in 6 months than what my father would make in the single highest earning year in his whole life – and that wouldn’t happen for another decade, when he topped out at $33,500.

You bet your ass I was grown up.

My parents stole almost every penny I ever made as a child. Had it not been for the paper-tiger Coogan Law, I’d have lost everything that I would earn over the next 2 ½ years of working for Norman Lear. This larceny was unchecked by the State. Hell, it was APPROVED of by the court, who left me with the paltry sum of $20,000 when I turned 18. An amount that was further chipped away by the $2,000 delinquent tax bill my parents hadn’t bothered to deal with that I received as an Eighteenth birthday present.

There is no way to estimate the true figure of how much money my parents stole from me because they claimed I made different amounts to the IRS, the Courts, SAG, AFTRA, and to me.

How comforting to know that my parents were equal opportunity thieves who ran a racket and a half, and managed to get away with it.

Something that abetted their theft was that commercials were not covered by the Coogan Law at that time. So the parents of someone like me, who made a ton of money, weren’t required to do anything with the money but spend it on whatever they wanted.

My parents were more inclined to lie to the IRS than they were to lie to the Unions. They were more afraid of running afoul of SAG and AFTRA than they were of an audit, but not too afraid to have me do an appalling number of non-Union jobs that were never declared to anyone but my mother’s secret bank account and my father’s bookie.

My parents were bold about their lies to the IRS. In fact they lied about my earnings to the IRS from my very first job. They never claimed to the IRS any of of the multiple calendars, print ads or voice-over work I did before I had to join Screen Actors Guild in 1968, when I made $156 on my first union commercial – a long lost spot for Alpha Beta Supermarkets. It was only then they finally, reluctantly, filed taxes for me.

But here is my first ad from 1967:

My first job, 1967

My parents pretended I did no work and earned not one dollar in 1969, despite the continuing print work, and me having been the face of Ford’s Tot Guard (their first child safety seat) during its test run, and doing a non-union Gain Detergent commercial that played so much during the daily soaps I was recognized for the first time while in the grocery store when I was 5 years old.

They continued to lie to the IRS, and were so far on the take they never reported my first 5 years of AFTRA earnings.

I will never know how much I really earned by the time I’d gotten on to Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman. A conservative guess would be somewhere in the neighborhood of 250,000 of today’s dollars, if they had simply put it in a savings account and given it to me at age 18.

By 1976 my folks were in full swing, and had theft down to a science. Penn and Teller couldn’t make greenbacks disappear as well as Herb and Margaret could.

In 1976 I spent the full year employed under an AFTRA contract at a $750 weekly guarantee, there were summer residuals, as well as voice over promos for the show, which netted me upwards of $50,000. My parents declared to AFTRA I’d made $22,775.

My folks told Screen Actors Guild I’d made $32,500 in 1976. I was getting residuals for the 5 commercials I’d shot in 1975, with the Nestle’s $100,000 Bar spot itself bringing in a tidy $22,000.

Yet, it was declared to the IRS that in 1976 the grand total of my earnings was only $15,300.

They’d declared more than $55,000 in earnings to the Unions on who-knows-what actual earnings, and somehow I wasn’t audited for my parents asking the IRS to believe I’d made less than $300 per week as a main cast member on a screaming hot television show.

This mind boggling shell game continued until the show ended in 1978.

Using my tax returns I can see that my parents admitted to stealing $750,000 from me. Remember, this what they admitted stealing, and is only the earned income that I would have received at age 18. I would have had so much more had it been invested with a reputable money manager starting with my first job at age 3, in 1967.

What about the money my folks stole over and above what they declared to the IRS? Your guess is as good as mine. They consistently under-reported my income by 50%, sometimes by 100%. It would be reasonable to say I earned 2 to 4 times the amount they declared for me. Somewhere between $1.5M and $3M 2018 dollars, and not a dollar of it invested.

By rights I should have been a wealthy young woman when I tuned 18. It seems that for a lifetime of work and foregoing my childhood I should have had more to show for it than $1,000 a year. I can only imagine what my fortune would have been had they done the right thing.

All that was left of my meager Coogan account allowed me to pay for 3 years of college tuition, while I worked to pay rent on my apartment. It also allowed me to move to Colorado in 1984 at the ripe old age of 20, and set out towards a place with mountains and skiing, far away from my parents.

Picture this – It’s 7 am on the first Saturday in June, 1984. *Knock Knock* “Mom, Dad – don’t get out of bed. I’m leaving for Colorado. No – really. Don’t get out of bed. My car is packed and I’m on my way. Buh-bye.” I was out the door like my ass was on fire.

Happiness was Hollywood in my rear view mirror.

Within 2 weeks of leaving LA I had a job that covered all my bills – I was teaching acting in Denver.

I also used the money from my Coogan Account to buy my first Subaru – a Brat that I adored and that defined the new Claudia I’d become when I left Los Angeles.

Finally, I used the remainder to put a down payment on my first home.

I remember my mother wistfully opining in the waning years of her life, as she lived like the Merry Widow and denied the single request for help I’d made as an adult at Christmas in 1999, “It’s a shame you wasted your money from Mary Hartman.

My parents stole an unconscionable amount of money from me without batting an eyelash – and stole my childhood as well, and there is no way to forgive that. None. The healthiest thing a child performer who has been cheated can do is come to terms with it through therapy, or it will eat you up.

Every generation has child performers whose parents treat them like nothing more than a fountain of money. No matter what the law intends, every generation of greedy stage parents will find a way to steal from their children by exploiting loopholes and the lack of laws. My heart goes out to current child performers whose every move is being documented for Youtube fame, in hopes they will become the next Fountain of Cash, and their actual childhood is being monetized with absolutely NO oversight.

There are times when I think back to that night at Diamond Jim’s. That dinner really meant something special to my parents. It was the validation of all of their hard work at marketing their children and what they’d been working toward: One of their kids was good enough to land a national television series.

It meant a spigot of cash like nothing they’d ever seen had just been turned on. As far as they were concerned their income had nearly quadrupled in one fortuitous afternoon. What was not to celebrate? They were positively kicking up their heels

At least that night I didn’t know my parents were stealing from me, and I thought the celebration was for *my* accomplishment. That was one small mercy the universe extended to me.

November 18th, 1975, Joan Darling handed us all a small blue box before rehearsal. The gasps from the folks around me let me know it was something special. I untied the thick white ribbon, and greedily opened the tiny box to find a felt bag emblazoned ‘Tiffany & Co.’ Inside was a key fob with a charm that said “MH, MH” on the front and “11-18-75” on the back, the date when we all set to work to make the best goddamn television show in the history of ever.

I will be forever grateful that I was part of that amazing company of actors, and that I had the privilege of learning comedy from them, and performing with them. Fortune was on my side when I think of the kind members of the crew like Susan who shared her gum, and Billy and Rick who taught me to operate a boom, and Harold who used to hide treats in the prop room for me to find.

I am thankful my teacher Joan indulged my love of reading, and made me actually learn and think about my future, and she took me to museums and to Star Wars and decided that watching Bob Hope rehearse with Donny and Marie one afternoon was a fine education.

Most of all I know that the time I was on Mary Hartman was where I began to write, and that writing was instrumental in every job in my adult life. The IBM Selectric typewriter Norman Lear had delivered to my schoolroom was a magical beast that allowed me to put my thoughts down faster than I could write by hand, and it opened up a whole new world for me. The classes I was able to take at age 16 with writer, and MH2 program consultant, Oliver Hayley convinced me that I could tell a story.

It has been a long and interesting path since then, and all of these people and their kindness helped me lay a foundation to build a path to get out and away from my toxic parents. I remember selling my first joke, opening the mic on my first full-time Talk Radio show, publishing my first article, anchoring my first newscast, and winning my first Mark Twain Award for excellence in news.

It’s wonderful to think that the path away from the biggest abusers in my life began 43 years ago with the people who would forever change how I laughed and cried and looked at life.

Love is marvelous that way.